“I think truly tasting is a difficult thing to do.”

08.17.19

John Birdsall is one of the most quietly influential food writers working today. In a noisy media landscape, Birdsall gives the reassuring sense that he’s not trying to land a gig as a reality-show judge or launch a podcast—but simply write careful, original commentary on the way we eat. In his prose, food becomes a portal to delve into the cultural consciousness. “I want to look at this romantic notion that food can be a vehicle to load all kinds of emotions and desires that cannot be expressed any other way.” After 17 years as a professional cook, Birdsall moved from the pan to the pen reviewing at the Contra Costa Times and East Bay Express. Recently, he’s staked out a reputation as an essayist winning two James Beard awards for his articles on the influence of gay cooks on American dining. Currently, he is working on a biography of James Beard himself. More than a historian, Birdsall is the intellectual godfather of a nascent movement of queer chefs and food critics who increasingly connect their identity to their eating. Yet it is a mistake to pigeonhole his work into any subgroup. In a hyper-ventilating food culture, driven by the frenetic pace of restaurant publicity, Birdsall’s writing offers a welcome counter-weight: an invitation to slow down and see the forgotten story in the food around us. I met John Birdsall at the North Light bar in Oakland. His hands were never still. You get the impression his fingers—and his mind—never stop moving. Often, while answering a question, Birdsall broke eye contact to look down at his fidgeting hands as though they were shaping some invisible mental clay, smoothing the rough edges of a wayward thought into a polished idea. We had a wide-ranging conversation that roamed from the literary character of the restaurant critic to Texas Lemon Cake’s role in the great gay diaspora.

1. THE CHARACTER OF THE CRITIC

Ted Gioia: How would you define good food criticism in your opinion?

John Birdsall: More than anything successfully putting a meal and a place into context. And that can be really challenging. The best criticism has a sense of really explaining an experience, explaining the historical moment that the restaurant finds itself in, and all of the cultural elements that it draws out. It’s a complex mix of history, culture, and just knowledge of food as well—being able to communicate what it’s like to taste.

TG: How would you differentiate good food criticism from good food writing?

JB: Obviously, criticism has a much more limited goal. Food writing is so diverse. There’s even some people who don’t like to call themselves “food writers.”

TG: Yeah, the infamous food-writer label.

JB: I actually like it and wear it with pride. But I think food writing in general can be anything from memoir to journalism, and the range and scale of those things is often not very exact. It really is reporting in a different way. It has a much broader aim than criticism. Within contemporary currents, there’s a similarity in the styles of criticism but a much broader range of food writing.

TG: One advantage of food writing is it’s a hybrid form where you can bring in a lot of different styles, voices, and genres. What topics do you think we should be writing more about in food criticism? And what do you think we should be writing less about?

JB: It’s such a fraught moment in criticism right now. There’s so much emphasis on the point of view of the critic. So all the cultural assumptions that a critic brings to the piece come under scrutiny. A long time ago, there was a goal to be somewhat transparent—like he or she wouldn’t necessarily bring a personality (certainly not an overbearing personality) to the work. When that style changed, criticism became much more about reporting an experience with a strong voice and a strong point of view. Then, all the sudden, questions arose about the critic’s experience and cultural assumptions.

TG: Something that’s always interested me, as a literary critic, is why there’s not more discussion about the creative form of criticism. How could you reimagine the literary format of the restaurant review? For example, why not frame a review as a Platonic dialogue between two people rather than a monologue? Perhaps by questioning some of the basic assumptions about the template there are ways you can expand the possibilities of discussion.

JB: When I was starting my first real gig, I did a weekly restaurant review for what was then the Contra Costa Times. I had this really indulgent editor who was like “just go for it.” I would set little assignments like I’m going to take a conventional review and then flip it. So I would write a review that starts with traditionally the end of the review—starts with beverages or dessert and then goes backward through the meal in a way that the reader wouldn’t notice. Or write a review as a series of 10 crucial points about this restaurant.

TG: You’re speaking my language right now.

JB: But the Contra Costa Times was a more conservative audience. There was always lots of pushback from readers. I remember this one review of a pho place where I kind of seized on the server, who had a kind of half-finished dragon tattoo that I started using as a recurring metaphor. This one reader wrote back, “If you want to write a novel, write a damn novel. Just tell us if it’s good or not.”

TG: I guess that’s the dilemma. Restaurant reviews are trapped between service journalism and literature. How do you provide both? Or do you pick one? “Fraught” is the right word.

JB: Sometimes in my pieces at the East Bay Express, my editor Michael Mechanic was just like, “Do you like this?” I was spending all this effort trying to describe something concisely, but I’m not sure if it’s good or not. I’m not sure if I like it. Sometimes, I didn’t want to say, didn’t want to be pushed to deliver that basic service piece.

TG: In a funny way, I feel it’s irrelevant if I like something or not. It’s about whether the dish stirs certain emotions or conjures the kind of experiences worth describing in detail.

JB: I recently read a talk that Jonathan Gold gave to a class at USC about food writing and criticism. He sort of told them: It’s not about you. Whether you like it or not in some way is irrelevant. It’s not your job to say whether you think this is good or bad. Your job is to explain what this is, explain how the restaurant does what they’re trying to do, how successfully they are doing what they’re trying to do, and then just putting it all in the context of what part of the city it’s in, what tradition it fits into or stands against.

TG: It’s the difference between a critic as arbiter and the critic as a cultural anthropologist.

JB: Right. There are conflicting fashions in food criticism as well. There was a movement in the late ’60s to reimagine restaurant criticism. There were two kinds of criticism. There was the establishment criticism, especially Craig Claiborne from the New York Times. He wrote about all kinds of restaurants, but he was seen as the arbiter of the highest expression of cooking in NYC (which was French cooking at the time). Everyone knew Claiborne. So in response there was an effort to get a more accurate, consumer-friendly read of those restaurants. If you just go in, how do you get treated? There’s the famous Ruth Reichl review of Le Cirque from the New York Times, where they served her before they knew who she was and after they recognized her.

There are all kinds of problems with it, but Reichl puts it over because the voice is so appealing. She just makes you relax, and you always believe in the persona. Which is definitely a persona. It’s like: “Oh, I don’t really belong here anyway. I’m just a regular person. I feel much more comfortable at a dinner party around my funky Berkeley table.” And you buy it.

TG: In a strange sense, becoming a restaurant critic more than any other type of critic (like a book reviewer or movie reviewer) is the creation of a literary character.

JB: Yeah, I think that’s what Reichl brought to the field. She really did bring literary style and sort of created this literary narrative. It’s still consistent. In her latest book Save Me the Plums, it’s that same persona that she’s had for 40 years. It’s quite impressive—merging this literary sensibility with a service genre.

2. DOES GAY FOOD WRITING EXIST?

TG: You’ve theorized a lot about gay food writing. Do you think there is a gay sensibility in food writing? If so, how would you describe it?

JB: Yes, I think there is. I’m working right now on a biography of James Beard, who was considered the grandfather of American food in the 20th century. I’m very interested in the question of how the way Beard dealt with his sexuality in his life informed what he came to know as American food. I think one of the ways historically that people have struggled with it—and it still plays out today—is the sense of voice. There was a male voice for food writing and a female voice for food writing in the 20th century. When they began to merge or blur, it was problematic for editors, publishers, and for some authors like Beard who didn’t like that distinction.

TG: The “Food section” in the New York Times was originally called the Woman’s Section.

JB: It was. There was also a pretty vigorous genre of male cookbooks and male food literature if you go back to the 1920s in the United States. But it followed strict rules. Men were allowed to be gourmets. They were hobbyists. As part of the structural misogyny of the time, women had to get all the food on the table. But men were the real artists. They were very methodical and men could produce things that women were incapable of. Also, there’s a firm genre (which even MFK Fisher wrote in at some points in the 1940s) of male food literature as a seduction. The idea was that men cooked to seduce women. That they would fight over a woman they cooked for, and it would be this powerful seduction.

Then you had a couple authors who didn’t write in that traditionally accepted male space, but wrote about more practical cooking in a way that women always had (like the Betty Crocker staff writers who were all women or were all presumed to be women). There’s this interesting overlap between that very gendered voice and the gay sensibility. There was tremendous anxiety about this. Nika Hazelton, who was a food staff writer for the New York Times, did a column about cookbooks by men published that year. There was Michael James, Craig Claiborne, James Beard, and a few others. And she was trying to make a joke when she said something like: “So what is it about all these men writing cookbooks? How do we think about this? Is the kitchen apron just a new kind of transvestite-ism?” This was 1965. So there’s an anxiety about this violation of gender roles, while in the 1930s and during the Second World War, there was a loosening of genders roles.

TG: Right, by necessity.

JB: Even in the 1930s with socialist currents being kind of mainstream, there were all these questions arising on the fringe about the best way to have a modern society. Does it make sense for there to be a nuclear family where every apartment in the building needs a kitchen and every woman in that family needs to be cooking? Wouldn’t it be more efficient and allow women to do more meaningful work if there was a central kitchen who could cook for an entire building? These were the sort of things being discussed in New York. Then after the war things got extremely conservative, and gender roles became very circumscribed again. It became part of this postwar patriotism to act in prescribed ways, and it was hard to step outside of that. These male voices—most of whom were gay (even though they were closeted)—were writing at a moment where there had to be these elaborate structures to explain inveterate bachelors.

TG: This is leading right into my next question. You talked about how queer food writers have fundamentally shaped Americans’ view of food, particularly highlighting a theme of a healthy hedonism. James Beard was especially important in this regard. You wrote, “Craig Claiborne gave us the permission to respect pleasure and eating, not as something guilty but as received wisdom of the culture, James Beard made it okay for Americans to be hedonists at the table.”

JB: I think my understanding of that is now more nuanced, because there were plenty of women who were advocating similar things. While there were women working in the traditional home economy (which was more about thrift and less about pleasure), there were plenty of women advocating for pleasure as well. In a way, it was more acceptable for men to do so because there was a tradition of gourmet male cooks making elaborate recipes as something that was manly. It was what you cooked on Sunday.

Beard had to live a lot of his life outside the US. It was easier to live in America as a gay man before the Second World War because there was a kind of openness (especially in New York City) that ended after the war. There was real fear — I mean REAL fear — of being prosecuted. So if you had the means to leave the country, you would. So Beard would make at least one major trip outside the US to Europe every year. He’d go to France, Italy, Spain just to get away. Tennessee Williams did the same thing. France never had sodomy laws. Italy and Spain were so disorganized that you could have a lot of latitude. Also, Beard just needed to get away to be at least somewhat anonymous because his image became so well known in the US. Plus, he was hard to miss anyway since he was just so enormous.

Immersing himself in these other places informed his idea of who he was. He used principles and cuisines from other countries to create this very convincing hybrid of American food—based on French cooking but combined in a certain way and using certain ingredients. All of a sudden, these principles became American. They centered on pleasure and this pure love of ingredients that had existed in the gourmet movement in the US, but now existed in a new way that sought to focus on much more practical cooking than MFK Fisher’s approach (which is far more literary). Beard was like, “You can do this every day. You just have to try a little harder.”

TG: It sounds like you’re a little uncertain if there is a truly gay sensibility in food writing?

JB: I mean, I know that there is. As a contemporary expression, I’d look at Nik Sharma. I’ve never spoken with Nik about this, but Nik has this way of spanning gender in his cooking, his writing, and his approach. He’s like this total Earth Mother, sort of gardening and raising cats. His whole approach to food defies genre, and I see that boundary-breaking as very much a part of this tradition of ignoring gender lines.

TG: I had never thought about that. A lot of gay creators borrow different aspects of gender to help them express themselves and that gives them a certain amount of freedom and fluidity.

JB: Yeah. Greenwich Village, before Stonewall, was sort of a safe enclave for gay men and women of a certain class. It was a place where people could move from all over to be “you” and to feel safe. But they had very rigidly segmented lives. Outside the village was nothing like inside the village. For instance, especially in Beard’s later books, I can identify recipes that came from specific gay friends.

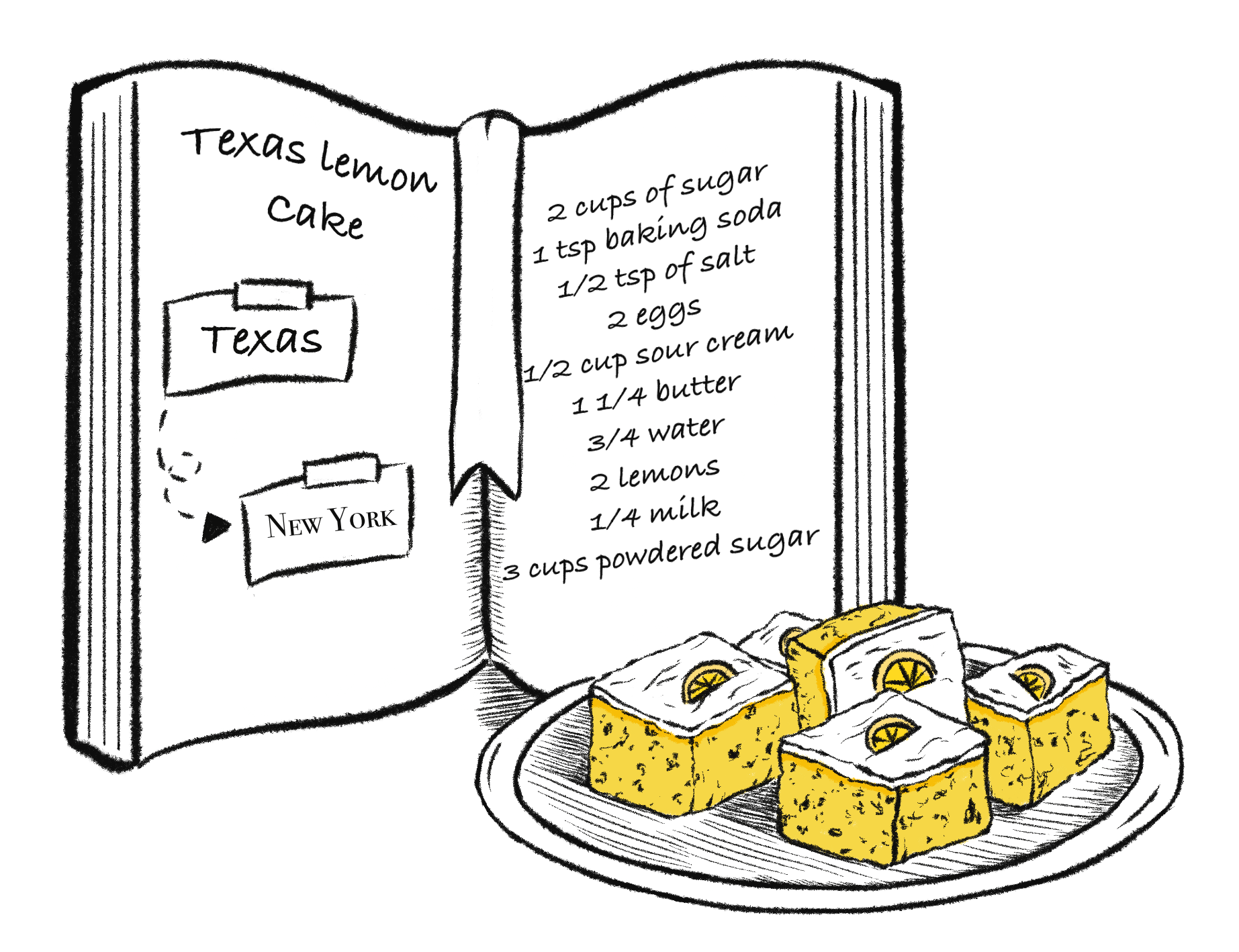

In this context, we have a recipe for a Texas lemon cake and the headlines would be, “this is from an old family recipe.” Well, yes, but the way it got there was because a gay friend of his had to leave Texas and brought his grandmother’s famous lemon cake when he moved to New York City. So the recipe has this residue of a story of intentional family. Really everyone Beard socialized with in a personal way was gay or lesbian. People who weren’t tended to be his editors. There’s this firm sense of a very close family. People brought recipes from all over, from wherever they grew up and had to leave. So there’s this bittersweet quality to the recipes: the sorrow from being exiled from your hometown and family but also the joy from creating a new life in New York embodied in artifacts that spanned these two worlds—artifacts like your grandmother’s Texas Lemon cake. So what looks like Beard’s exhaustive research into American cooking in a lot of ways is just stuff that was brought to him through this gay migration to the cities. It has a poignancy about it from this lingering sense you get of the great gay diaspora.

TG: How do you think your sexuality has informed your writing? I know at the surface level you’ve been writing about James Beard and other gay figures, but at a deeper, more personal level do you think it has?

JB: I think at the deepest level it has. The stories that tend to interest me are people who come from traditions that reject them but still feel connected to the foods that express the life that they’ve been exiled from. In a more subtle way, I’m very interested in the role of queer people as keepers of culture—that sort of third-gender idea. They are the group of people who teach children, teach them the songs, the dances, and the stories. But they still exist apart.

I’m fascinated by men like Beard and Claiborne who were freed from the gender baggage of what was expected of women (having to get 3 meals on the table for your family every day, whether you enjoyed it or not). Cooking, liberated from that domestic expectation, could become more expressive. So, to me, this sense of food as an expressive medium is a hallmark of queer cooking.

TG: A lot of this resonates with me. Though, I must admit I was a little skeptical when I first read your essay from Lucky Peach that described salads as “thickets of yearning.” That’s a bit too much for me. But then I thought about it more and realized that the queer sensibility to me seems inescapably connected with a certain way of luxuriously describing food—observing certain qualities or facets that someone else might miss.

JB: I think that’s true. I want to look at this romantic notion, this idea that food can be a vehicle to load all kinds of emotions and desires that cannot be expressed any other way.

3. CUTTING OUT THE CLICHÉS

TG: How do you try to describe food? More pointedly, how should we not describe it?

JB: That’s a hard thing. There’s so much. Describing taste is challenging because there aren’t that many words. I remember Jonathan Gold saying you can play with your thesaurus and try to come up with different ways to say “salty.” But it just doesn’t work. At some point, you just have to say “salty.” I think cutting out clichés is a really basic thing to do to improve the way you think about food. It’s actually harder than you realize. I always think “I’m going to cut out all the clichés” and then on the third or fourth read of something you’re like “oh Jeez.” You’re so wired to use certain words and phrases.

I think truly tasting is a difficult thing to do, like really diving into the taste of something. It takes a lot of attention, and it’s especially difficult to do that in a restaurant setting. Overall, I’m more interested in describing food as part of a narrative. “Thickets of desire” fits into that. Food is never a static thing. Food is always part of some narrative experience—

TG: –So the qualities you project onto food.

JB: –Or the way that it defines or stands in opposition to a prevailing feeling or mood.

TG: Is there any particular word that you think should be retired from the food critic’s vocabulary?

JB: I don’t think so. I mean you could pull out specific words such as “scrumptious” and stuff like that. But I think anything potentially works depending on what you’re trying to do.

TG: Are there any words that particularly bothers you?

JB: Things like “scrumptious” that are trivializing food. Things that don’t seem well thought out. Sort of cute. But I can see using those words when you want to evoke a certain character or mood.

TG: Final question. Just to toss a softball, right down the middle: How do you hope the future of food writing will evolve?

JB: I’m in an ongoing conversation with a couple of food writers on Twitter about this topic. Right now, there’s a lot of good food writers, and a lot of potential for good food writing. But I think the level of editing is very poor. I read so many pieces—and I’m sure I’ve written so many of those pieces—where it’s like 2/3 or 3/4 of the way there. You’re like “Aahhh, NO! This has to go farther here, and this has to pull back. They didn’t challenge the writer to take the next draft deeper.” With budgets and time constraints, I know only so much is possible. But I would really wish for more professional editing—the kind of editing and publications that can truly bring writers out and develop them.

I think the whole question of diversity that food media is struggling with is very painful at the moment, but I’m fairly confident that it will end up in a better place. I think it’s a matter of getting other people in the roles of editor and publisher. Right now, it’s pretty much the same white boy. So there is a diversity issue. But at the pure writing level, I’d just like to see more originality. My whole thing about cliché: It’s not just about word choice. It’s about assignment.