“A lot of people say that food brings people together. I don't believe that.”

07.22.19

Nik Sharma wants to retire the adjective “traditional.” “I see books that claim to be ‘authentic’ or ‘traditional’ recipes in their subtitle. That makes me very uncomfortable because at the end of the day, a recipe is something that is dynamic and evolving over time.” Indeed, there is no single static tradition that can contain the dynamo of Sharma’s cross-continental imagination: Sharma is a gay, Indian, immigrant food writer and photographer who has skyrocketed into one of the most original voices in the Bay Area culinary scene. Growing up in Mumbai to a Roman Catholic mother and a Hindu father from the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, Sharma’s childhood table was a daily lesson in cultural exchange. After leaving his job in the pharmaceutical industry, he built a dedicated following with his acclaimed blog “A Brown Table” and his cooking column at the SF Chronicle which delicately mixed photo-journalism, cookery, and cultural archaeology. Sharma captured attention for his quietly iconoclastic recipes that put Indian cooking and ingredients in conversation with American cuisine in a style that feels refreshingly contemporary. “I’m always trying to showcase the versatility and adaptability of my culture in India within my culture in America.” This syncretic ethos flows throughout Sharma’s gloriously diverse debut cookbook Season, which tells the personal story of his journey from Mumbai to Oakland through cooking. Sharma tries to show how we use food to “creatively explore our world” and navigate the uncertain crossroads of identity. Each of his recipes and columns vibrates with this tension—the tension between tradition and invention, convention and innovation, between respecting the past and daring to invent the future. Ted spoke with Nik for 30 minutes about the challenges of escaping tradition, debating the existence of “gay” food, and whether you can make a Vegan Vindaloo.

1. TELLING NEW STORIES ABOUT INDIAN CUISINE

Ted Gioia: Let’s hop right in. How would you define good food writing? What’s the goal of good food criticism to you?

Nik Sharma: The writing that I find the most valuable is the stuff that I still remember a week or even a month or a year from now. Usually, those are the stories or the essays that have something of value that I walk away learning a new perspective on something that’s been written about in a hundred different ways. But it’s a new perspective. You walk away being more knowledgeable than before you read it. Those are the stories that move me personally, the ones that aren’t the usual tired tropes yet at the same time have something to add to the conversation. Not building from what’s been said before but actually creating something new.

TG: Are there any essays or pieces in particular that you remember years after reading them?

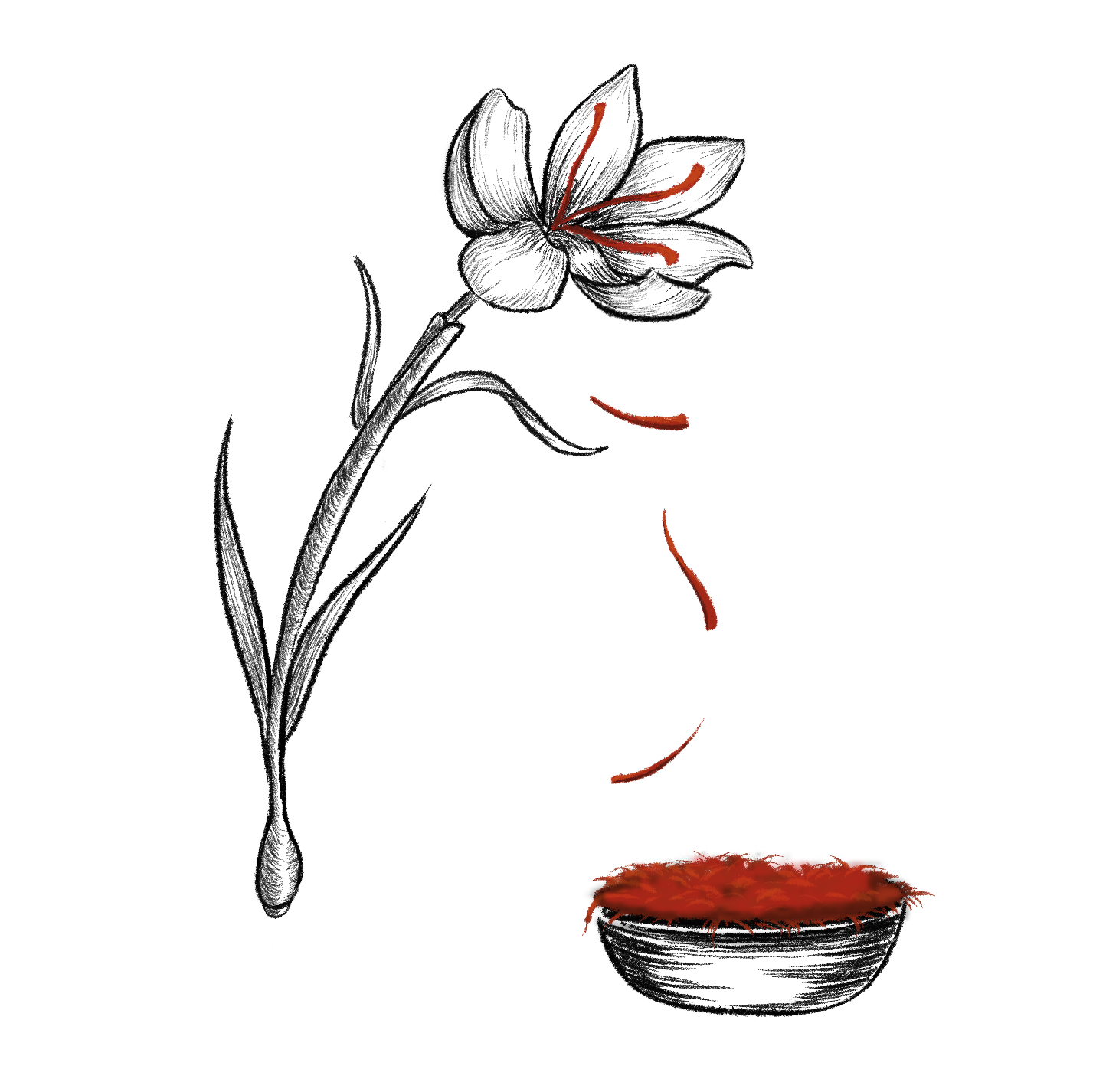

NS: There was a story that came out a couple of months ago on Eater about saffron in India by Sharanya Deepak. I thought that was an interesting perspective. Having grown up in India, I know that saffron farmers both in Iran and in India are producing this extremely expensive spice—which is highly prized and valued—but the quality of life is precarious from the fact that they are in war-torn areas. No one really stops to think about it. Then you have the other side of the problem when people are now trying to grow saffron locally in other countries, which is taking away income from these people. This is their only source of livelihood, so not only are they losing their lives in war but then you have this other economic problem arising. So they’re fighting all these different things and nothing good is coming out of it. But it was really refreshing to see that perspective being shared since it’s not really written about much.

TG: Along those lines, what topics and perspectives in food should we be writing more about? And what topics should we be writing less about in your opinion?

NS: Well, I can speak about the stuff that really excites me. I hate rules when people say this is what you should write about because that stifles creativity.

TG: Right.

NS: At the same time, there should be some focus because often the best stories are personal essays or something about a region or a culture that’s not written about. For example, I think one of the stories in Indian food, which I can relate to, is the fact that everything written about curry will be from the Indian standpoint because that’s what people are comfortable lecturing about. But no one really writes about the food coming from different parts of India. So there’s a blanket statement that seems to pervade Indian food, which is more of a north Indian, Hindu cuisine. Now you have a little bit creeping out about south Indian food. But beyond that, there’s not a lot and that seems a bit odd to me because India has one of the most diverse economies in the world with a lot of different faiths, a lot of different languages spoken. And to expect everyone to behave in a specific way doesn’t make sense to me. Why would people expect and want that?

2. THE AUTHENTICITY TRAP

TG: How has sexuality influenced your writing and your perspective on food?

NS: I think it would influence anybody’s perspective. But I struggle with this a little bit because I don’t know what makes a dish “gay.” What does matter is the fact that [your sexuality] influences your thinking in a different way. You start to connect with certain things, based on certain events that happened in your life. In my case, food is my medium to tell those stories. So, to me—yes—I feel it does play a role in shaping how I think about ingredients and food. Sometimes it can be metaphorical. For example, that essay I wrote for the Chronicle about the fig. But I think it is difficult to discuss sexuality in terms of food without having context. When you’re talking about recipe or a dish there has to be context to the story of how the dish came about, and that kind of builds the stage for that narrative.

TG: Yeah, even as a gay man myself, I’m a little skeptical when people talk about “gay” food. What does that mean? Is it just penis-shaped perishables? If I were to stretch, I suppose in my own writing, I’ve found that being gay has influenced the way I approach creativity from an outsider’s perspective. It’s a subtle influence. It’s difficult to articulate, but I also think it’s interesting to tease out to see if there are some common principles or philosophies that people share. Are there any dishes or ingredients that you remembered approaching differently in some way because you’re queer?

NS: Not really, to be honest. I don’t think I’ve consciously paid attention to a technique. But it can happen in the moment, and then 10 min later I actually make that logical connection. In general, I can say that being gay (and also being a person of color and an immigrant) has made me much more sensitive to certain issues in food media. I feel because I check all these boxes—not by choice, you know—there’s always pressure on me to perform better than everyone else. Because if I don’t perform, they’ll think less of me. There will be more latitude and freedom given to someone else who is white and gay or white and male. I won’t get much room to make mistakes. So that makes me strive harder to be better at my craft.

TG: That’s interesting. The representation pressure is intense. On a different note, in a recent column you gave a powerful analogy that a recipe with proper context is like a string for a kite while a recipe without context is like a kite without a string. I was wondering how you approach the recipe as a literary genre?

NS: Yeah. I often come back to something that Tejal Rao said once—I don’t remember if she wrote or tweeted it—along the lines of “I’ll always write so that I would want to read my story again.” So I keep that information in mind because I personally can sometimes get lost in trying to convey something complex that might mean nothing to other people. So I try to focus on giving a perspective that’s much more. But I try to make tangible it for everybody because I don’t want people to get defensive, that’s the worst thing when you’re trying to convey something nuanced.

TG: Yeah.

NS: A lot of people say that food brings people together. Actually I don’t believe that. I think that’s very misleading, because people can fight over the smallest things in food. Like Veganism, for example.

TG: Indeed. Food brings people apart with veganism.

NS: It’s not true that food brings everyone together. That’s a very romantic notion. At the same time, I would like people to be able to say, “This is something I agree with. This is something I don’t agree with, and that that’s fine.” People shouldn’t have to agree with everything I say, or someone else, but it should be done as an act that’s congenial and comfortable so the conversation actually moves ahead and they’re not stuck. So I try to do that with my stories. I’m just opening up and being vulnerable. I’ll share “this is something that I went through” or “this is something that I’m thinking about.” At the same time, I try to be open and make room for other opinions from readers to say hey, but this is where I’m coming from so I can understand a new perspective too. Because while I’m trying to educate people, I also need to learn and educate myself by listening to their experience.

TG: How would you say writing about a dish is different than photographing one? Is it a different creative process for you?

NS: It may be a bit similar. When I’m creating a dish, in my case, I’m always trying to showcase the versatility and adaptability of my culture in India within my culture now in America. So I’m always trying to put both of those things together. When it comes to photographing, I try to do the same thing because I want people to get away from the stereotype of what’s portrayed in food photography for a certain culture. For example, with Indian food, you’ll often see props used to create this narrative of what you might fantasize Indian food to look like in some Indian person’s kitchen in Mumbai. I try and stay away from that. I used to do that when I started out. So I’m not a saint. But as I learned my craft and understood what I wanted to tell people, I started to move away from those clichés. At the end of the day, in a culture, things have to move forward in a direction, and I need to be open to change if I’m going to be an advocate for it.

TG: Are there any particular phrases or words that you try to avoid? What word do you wish would be banned from the food writer’s vocabulary? I think of using the adjective “exotic” for cuisines that are not European. Sorry, I know it’s a very provocative question.

NS: No it’s ok! Let me think. Sure. I definitely avoid “exotic.” I’m not a big fan of the word “ethnic” in most situations. It makes my skin crawl. It’s kind of like when they do those regressions where if your skin color is white, then your value is equal to 1, and everything else equals zero. It reminds me of that.

But the other thing that I try to avoid is “traditional” and “authentic” because I feel those words are used to diminish people. I don’t know if restaurant critics actually use those words, but if anyone is they should probably retire them. I see books that will claim to be “authentic” or “traditional” recipes in their subtitle. That makes me very uncomfortable because at the end of the day, a recipe is something that is dynamic and evolving over time. What you would eat a hundred years ago, you’re probably not eating the same thing now. When you cook, those recipes change and evolve, so to claim that something is authentic or traditional is kind of silly.

Also, traditions are something that are built over time, right? You learn something new, you like it, your family likes it, so you decide to do it again and again. And that becomes in its own way a tradition. So to claim that your recipe is “traditional” is this weird badge. People want to hold onto it to give the appearance that my recipe is better than yours because it’s “traditional” and yours isn’t. But it’s kind of foolish to be fighting over that.

At the same time, it is important to acknowledge the history behind a recipe. That is much more important than talking about whether it’s authentic. Talk about the history of the ingredient. For example, pork vindaloo. I’ve written about this. Vindaloo was a dish that came to India, to Goa, because of the Portuguese. Vindaloo was not something that Indians would eat. When Portuguese brought vindaloo, they brought lots of meat (especially pork) to the Indians who were living in Goa, and because the Portuguese were traveling on ships for long distances they used vinegar to preserve meat. Pork was the choice and that’s how vindaloo came about. So the entire chemistry of that dish is based on making meat more soft and tender by using a low acidic pH vinegar.

So to then suddenly make vindaloo vegan, to substitute chicken or tofu, if you were to hold onto the same recipe technically it won’t work. At that point, it’s just a curry with vinegar or a sauce with vinegar. It’s not really Vindaloo. Those are the things people need to talk about more rather than focusing on the specifics of what is “traditional” or “authentic” because that’s when these problems in food arise.

TG: It’s interesting you say that because one thing I often think about is the current battle over the title “meat” or “cheese” or other dairy products. There are a lot of Vegan products that advertise themselves as a “meat” or “cheese” substitute or something like that. To me, I always wonder: Why don’t they just think of a new term? Why not just invent a new word for their product? But it needs to pose as this other substance and that confuses the tradition behind crafts like cheese-making and butchery. Why not establish your own Vegan tradition with your own unique recipes?

NS: Yeah, I think that’s fair. You should be excited about what you’re creating that’s new. So don’t diminish it. Just say you got the idea from them, and then call it whatever you want. But to pass it off as something that becomes a blanket statement, then people started expecting that and it becomes very difficult to go back to the history. It becomes difficult to go “Well, this is actually what it is.”

TG: It also creates backlash. Last question: how do you hope the future of food writing will evolve in the next 15 years?

NS: I can speak for Indian cuisine. What I’d like to see is a wave of new voices talking about the food that even I haven’t heard about, the food that’s not coming from a place of the sanctity of what India is. It shouldn’t be like—what is that movie—Jewel in the Crown? Something like that. [laughs.] I don’t want those kind of images to be portrayed. Historically, those things are important, but at the same time I think people need to talk about the other things in India. And I think people would want those stories too because it creates a richer environment. Then you learn more, and you taste new things. Life is short.